* Ok, maybe not Everything but it’s a start.

I wrote this post in 2017 in response to some of the misinformation and ignorance that I’ve seen online and in the papers. Updating in 2023 I can’t help but feel that although there have been massive leaps forward, we are on the precipice of tumbling very far backwards indeed. This is a concern that should prompt us all to action. Hence I’ve updated this post to include discussion of co-governance, specifically address the use of Te Reo Māori, and my thoughts on the Aotearoa New Zealand Histories curriculum and mātauranga Māori in education.

If you’ve come through the New Zealand education system in the last 10 years you would definitely have learned something about the Treaty, but what and how you learned is sadly dependent on where you learned it and who taught it. If you came through the education system last century or are new to New Zealand, you might not have ever encountered the Treaty of Waitangi in an academic setting, and what you know (or think you know) is therefore shaped by the media and politicians.

I would like for that to change.

I believe everyone in New Zealand should know about, and engage in discussion around, the Treaty.

It’s interesting, it’s necessary, it’s ours.

Before we start I should share a little of my background, so you know where I’m coming from. I am Pākehā of Scottish, English, and Irish heritage. My family came to NZ from Paisley in 1845, and from the Scottish Highlands via Nova Scotia in 1857. I grew up in Central Auckland and went to high school in West Auckland. My high school was one of the very few at that time that taught 19th Century New Zealand History for Bursary in 7th Form. After I attained my Masters degree in History (my thesis was on Women Criminals in Auckland in the late 19th Century which was Super Interesting), I worked for the Waitangi Tribunal as a historian and a claims facilitator (you can find links to the reports I submitted to the Tribunal at the end of this blog). I then worked in finance administration in London (in case you think I’ve got some Ivory Tower Blindness going on). I have been a Social Studies and History teacher for 18 years and am currently Head of Department for History at a large and extremely diverse West Auckland school, where I also run workshops for our staff on Te Tiriti. I have therefore taught the Treaty of Waitangi to over 1000 teenagers over the course of nearly two decades – sometimes easy, sometimes hard. So while I certainly wouldn’t call myself an expert on the Treaty, I know more than many non-Māori.

I tried to come up with the questions that I’ve been asked over the years by students/friends/random strangers, or that I’ve seen raged about in media, and to answer them as best as possible in a succinct and easy to understand way. I think it’s important that we start from a place of knowledge, and if I can help in any way I feel it’s almost a moral duty to try.

This is going to be long, so grab yourself a cup of coffee and settle in, or spread the reading over a few sessions.

What is the Treaty?

I know, seems obvious right? You’d be surprised how little people know even after they cry ‘we learn this every year in school! I already know it!”. The Treaty of Waitangi is an agreement between Māori and the British Crown, signed on 6 February 1840. It is a short Treaty, as treaties go, with Three Articles. The Treaty is seen as the founding document of New Zealand, providing legitimacy for British colonisation. Despite this, it took a long time for it to be recognised in the new colony’s laws. It’s the only treaty I know of that deals with a presumed transfer of power rather than just land. You can read more about the Treaty, and read the text for yourself, here.

Why did Māori sign it if they didn’t want to give up their power?

Because in the Māori version, the one nearly everyone signed, they didn’t give up their power. They kept it. In the Māori version of the Treaty, in Article 2, Māori are guaranteed Tino Rangatiratanga – full chieftainship – ie, Sovereignty. This was what they had intended and, indeed, what much of the discussion prior to the Treaty centred on.

French missionaries present at the signing were recorded by the British missionary printer Colenso as saying: ‘the chiefs have no intention of ceding their sovereignty”. They wished the British to have kāwanatanga (governorship) over the settlers only.

Incidentally, this limited and nominal sovereignty is what Hobson had recommended to the Colonial Office prior to the decision to offer a Treaty. So basically, Māori signed the Treaty to allow the British to govern their settlers in New Zealand, to reaffirm their own power over their people and lands, and to guarantee that they would be treated fairly by the British. Not to give up their power.

Why did the British offer it instead of just taking over?

There are a lot of reasons for this, and some debate over whether their intentions were fully honourable. But at a basic level, taking over via military means would have been lengthy and costly. Remember that at this point, early 1840, there were an estimated 100,000 Māori in New Zealand compared to about 2000 non-Māori. Taking over by conquest was highly unlikely. Also, the 19th Century had seen a rise in humanitarian ideals, and more than one Colonial Office official had specifically mentioned a desire to avoid the situation that had occurred with Native Americans and with the Aborigines in Australia. The Declaration of Independence of 1835 (did you know we had one? Most people don’t) had been recognised several times by Britain, meaning that they had already recognised Māori mana o te whenua (sovereignty).

I recommend you read the primary documents leading up to the signing of the Treaty. You can find them in one of my favourite books: “The Treaty of Waitangi Companion: Māori and Pākehā from Tasman to Today”, edited by V. O’Malley, W. Penetito, and B. Stirling, published by Auckland University Press. I also highly recommend the new book by Ned Fletcher, lawyer and historian, “The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi,” which includes much discussion of Colonial Office intentions.

How many different versions of the Treaty are there?

There are two different language versions, the Māori and the English. Added to that, there were 8 copies made and taken around the country, meaning there are 9 separate sheets making up the Treaty of Waitangi. Not every iwi signed either; Tūhoe, Tūwharetoa, Waikato, and Te Arawa among them.

Which version is the ‘real’ one?

The Māori version is the one that is signed, so….

There was one English language treaty signed in Waikato-Manukau by 39 people. The rest of the 9 treaty sheets were in te reo Māori.

Also, an internationally recognised doctrine of contractual law called Contra Preferentium states that where there is ambiguity or conflict over the terms of a treaty or contract that the preferred meaning should be the one that works against the draftsman – the one who provided the wording of the contract. This means that the Treaty in the indigenous language is the one that must be given precedence.

Ruth Ross, in 1972, pointed out the differences between the two versions and argued for the Māori version to be regarded as the most authoritative. This became largely the historical consensus, with differences of interpretation limited mostly to whether the differences were from incompetence or a deliberate trick. Recently, Ned Fletcher has argued that the Māori and English versions are, in fact, reconcilable. His argument is, I feel, convincing, and turns on the fact that in the very specific historical context of British Imperialism in the early Nineteenth Century, the concept of sovereignty was less concrete than we imagine it to be now. At this point in time, British imperial acquisitions had a range of different kinds of rule, from indirect to informal to direct annexation.

- “The Māori text simply makes more explicit what was already implicit in the English text and well understood on the British side — that Māori self-government (rangatiratanga) can co-exist with Crown sovereignty (kāwanatanga).”

Fletcher’s argument is not dissimilar from my own interpretation, influenced largely by Colonial Office communications, but as a legal historian, he was able in his research to analyse how the legal understandings of sovereignty changed from 1839 to today. You can read an article summarising his argument here.

An additional point that Fletcher makes, is that when Busby and Williams were asked for clarification on various points in the years immediately following the signing of the Treaty, they both referred back to the Māori version. These were two of the most involved people in the drafting of the Treaty and they consistently referred to the Māori version as the authoritative one.

Doesn’t it just make us all One New Zealand?

Yes it does. In a way. And also no. The Treaty formed New Zealand and allowed new migrants a place here. It has the potential to foster a real partnership and an integrated society where all are recognised and welcomed. Has it always done that? No. In fact, through most of New Zealand’s history, the ‘One New Zealand’ in fact meant colonial Pākehā New Zealand. Māori, Chinese, and even the European Dalmatian gum diggers and Scandinavian migrants of the 1870s were seen as additions who needed to assimilate or have laws passed restricting their rights. Have a look at the 1920s White New Zealand immigration policies for further affirmation of this rejection of ‘one New Zealand’.

Yes, we are now one country and the Treaty was the reason for that. But this begs the question – what do we think our country ought to be?

Does the Treaty give Māori ‘special rights’?

Article three gives Māori ‘the same rights and privileges as British subjects’ in the English version and ‘promises to protect Māori and give them the same rights as British subjects’ in the Māori version. This is pretty extraordinary in a historical context. This is 50 years after Aborigines in Australia had been declared ‘fauna’ and 40 years before the Scramble for Africa and the 1881 Berlin Conference where European nations decided amongst themselves how they would divide up Africa between them. It was about the same time that Indians were made to bow to Englishmen on the streets of India. The working classes in Britain still were, for the large part, unprotected and disenfranchised. So, for me, this has always been a pretty extraordinary article. Unfortunately, it was broken a lot.

Māori weren’t able to vote under the 1852 Constitution Act because they owned land communally (incidentally this is the reason for the later creation of the Māori Seats for Parliament). They weren’t included in the Old Age Pensions in the 1890s or the new Social Welfare schemes of the 1930s because of a belief that their tribe would look after them. They were made to attend Native Schools rather than schools with the rest of the population. Their lands were invaded in the 1860s when they protested illegal sales and were later confiscated. Land in the Urewera was illegally surveyed and then lost to survey fees. Māori were denied the right to seek spiritual or medical guidance from Tohunga under the 1907 Tohunga Suppression Act. They weren’t allowed to speak their own language at school, and would get strapped for doing so. So the Treaty gave them the same rights, but a succession of governments denied them the same rights. And that ‘protection’? Not super evident.

But the ‘special rights’ that people usually mean are rights to land and fisheries. In which case – yes. Māori rights to these things are guaranteed both in the Māori version (Article 2 guarantees tino rangatiratanga remember) and also in the English version (Article 2 guarantees ‘full, exclusive, and undisturbed possession of their lands and estates, forests, fisheries and other properties”.)

Currently, in 2023, politicians and others have been slyly warping the meaning of Article Two of the Māori version, arguing that the ‘ordinary people of New Zealand’ who are mentioned are in fact all of us so that we all have sovereignty and there are no particular rights safeguarded for Māori. This is historically inaccurate nonsense. In 1840 the ‘ordinary people’ of New Zealand were Māori. They were referred to often times as ‘the New Zealanders’.

What about Hobson’s Pledge?

‘Hobson’s Pledge’ historically was a mere nicety in a ceremony. When the chiefs signed the Treaty at Waitangi, Hobson is recorded as saying ‘he iwi tahi tatou’ to each chief. This means: ‘we are now one people’. It was a nicety. It’s not a part of the Treaty. It wasn’t part of the discussions and promises beforehand. And again – what do we mean by ‘one people’? The people behind the current Hobson’s Pledge movement appear to really mean that Māori shouldn’t have their rights to their land, fisheries, taonga, or chieftainship. That’s a direct contradiction of the actual text of the Treaty so the ‘pledge’ is basically irrelevant. I would argue that it is a smokescreen for a desire for Māori to ‘get back in their place’ and assimilate.

What about the ‘Littlewood Treaty’?

The “Littlewood treaty” refers to a document found in 1989 that may or may not have been a copy or the first draft of the actual Treaty. It leaves out mention of fisheries and forests which is why certain people are keen on it. Apparently there’s a big ‘conspiracy’ by historians (*face palm*) in order to protect the ‘gravy train’ of the ‘grievance industry’. But the key thing to note – whatever this document is, it is NOT a treaty. It isn’t signed. By anyone. So it is an interesting piece of the historical puzzle, but not significant constitutionally. See this very clear analysis by Donald Loveridge.

Why can’t we just move on?

I get asked this a lot. My answer? If everything in our garden was rosy, if Māori did not face systemic inequality and injustice and if all grievances had been resolved – we wouldn’t be having this conversation.

The thing is that we can’t move on because we’re still in the middle of the mess.

It isn’t just that historical grievances remain unresolved, but that the impact of colonisation has meant that Māori have lower university entrance rates, higher mortality, higher proportion of prison population, and are over represented in poverty and poor health statistics. This is not a natural state. This is the impact of colonisation. It’s the same in every colonised country where the indigenous people are given second class citizenship.

Why have Māori just started being angry about it? Weren’t they ok before?

Another common misconception. No, Māori weren’t happy about the Treaty being broken. They’ve basically been protesting since 1842 and the Wairau Affray, followed by Hōne Heke’s famous chopping down of the Flagpole in 1844. They tried to reclaim their power during the 19th Century through peaceful means (the Kīngitanga, the Kotahitanga, Tūhoe’s Te Whitu Tekau, numerous petitions, letters, visits to the Queen, and Parihaka). They’ve also tried through war (although war was usually forced on them). The twentieth century, well before the 1970s and the Māori Renaissance, had multiple examples of protest and attempts to retain rangatiratanga. A few examples of key people in the early part of the 20th Century: Rua Kenana, the Rātana church, Te Puea Hērangi.

Māori have tried for a long time to make the Treaty partnership work. I’d say they’re long overdue for everyone else to at least meet them in the middle.

We are a multicultural society now, how does that fit with a bicultural Treaty?

Another common question, especially at a diverse school like mine. The answer I give is that the Treaty is between the British Crown (who is still the head of our Government) and Māori. It allows for Māori to be protected and retain rangatiratanga despite the influx of tauiwi (new people). We are all citizens of NZ, but NZ is a country that (according to the Treaty) includes a special partnership between Māori and everyone else.

Does this mean I’m not a real New Zealander?

Too often I’ve seen ‘real New Zealander’ attached to Pākehā New Zealanders or recent European migrants, so I’m not overly fond of the phrase. Many people of Chinese descent have families that have been in New Zealand since the 1860s, while some Europeans are second generation. Why is one seen as a ‘real New Zealander’ over another? *cough* systemic racism *cough*

There’s a Māori concept I came across during my research into Native Land Court cases in the Urewera: ahi kaa roa which means long burning fires – the right to land through continued occupancy. Like I said, I consider myself a New Zealander. My family has been here for generations. I will also say that when I worked for the Tribunal I attended many hui and visited many marae, and was never made to feel like I didn’t belong or that I don’t have a place in this country. Compare that to Māori being told that te reo Māori has no place on mainstream radio or television.

While I’m on this – the current backlash against te reo is astonishing to me. I thought we had moved forward. That said, I think we have. I think Dr Ashley Bloomfield’s consistent and natural use of te reo Māori in the Covid Pandemic 1pm Briefings made many people more confident to try using phrases like “across the motu.”

It’s just that the very loud racist voices are getting louder and have bigger platforms.

If we are all supposed to be embracing some kind of ‘real New Zealand’, then it seems bizarre to not embrace the language that no one else in the world has. Language is identity. This language, this inclusion of te reo Māori in English, is probably one of the few things that could genuinely create an authentic New Zealand identity.

One thing I’ve noticed – despite recent moves from the new coalition Government to remove te reo Māori from the public service, I see it more and more in the private sector. I don’t think the public is as supportive of this move away from te reo as certain loud voices would have us think.

So am I supposed to feel guilty for what happened in the past?

No, but you are responsible for what you allow to happen in the present. We are not guilty of our forebear’s actions, but if I don’t stand up to fight against the systemic inequalities that exist in my society now, if I don’t fight for the Treaty to be honoured now, then yes. I need to own that responsibility.

What if Māori weren’t the first people in New Zealand?

Firstly – all credible evidence points to the fact that they were. The conspiracy theories over this are too lengthy to discuss here but suffice to say they always remind me of those people who want to try and prove that aliens built the pyramids; it’s an attempt to deny Māori legitimacy and to devalue the Treaty.

Here’s the thing, though. Even if Māori weren’t the first people in New Zealand, that has no bearing on the Treaty of Waitangi. The Treaty was signed between Māori and the British Crown and is not dependent on Māori being the first people here.

Aren’t land claims just making new grievances?

No. The Tribunal can’t take people’s private land away. It has the power to recommend compensation or the return of certain lands, but the only binding recommendation re the return of land it can make is on former State Owned Enterprise land – land that the government owned. In contrast to this – you can have your house taken by the government to widen a road.

When will the claims process be over?

The aim was for the historical claims settlement process to be complete by 2020. See this post by the Waitangi Tribunal for current status.

This doesn’t mean that there will be no more claims – if Māori believe that the Government is breaching the Treaty they are able to lodge a claim with the Tribunal. This is an ongoing process to ensure that Māori rights under the Treaty are upheld.

Ok, but that was all in the past. Why should Māori get special treatment now? Isn’t that just apartheid?

When there are injustices, those injustices need to be remedied. Sometimes ensuring equity is different from ensuring equality. Preferential treatment/affirmative action is not apartheid (I think it’s deeply insulting to suggest it is and shows a severe lack of understanding of the history of apartheid), but a way to promote equity. This cartoon shows what I mean.

Once equity has been restored, or the systemic barrier removed, and Māori have their rights honoured, maybe then we can achieve real equality.

What’s all this Co-Governance stuff?

Co-governance is, in a nutshell, ensuring that the Crown and Māori have equal voice in decision making, in an effort to fulfil some of the promises of Te Tiriti. I recommend this very clear article for a short but more in depth explanation.

Former Minister of Local Government, Kieran McAnulty, when asked about the involvement of mana whenua in co-governance, pointed out that many local governments have no problem with the term co-governance because they already do it.

“We’ve had iwi representatives on local government for a long, long time. We’ve had separate Māori seats for a long, long time. There is a history of recognising the particular rights of Māori in this country, but I don’t believe giving Māori something necessarily takes anything away from the rest of us.”

He further stated: “We signed a treaty. The Treaty recognises that Māori have special rights, in water in particular, and that is something that’s been tested in the courts and found to be part of New Zealand law. When I was putting forward alternatives for cabinet to consider, I wasn’t willing to change on that, because I think it’s the right thing to do.”

However, you are likely to have heard about co-governance via the very loud movement against it. A very vocal Julian Batchelor has led many Stop Co-Governance rallies around the country and has published and distributed around 350,000 28 page, colour, booklets of his views on Co-Governance. One wonders where the money for this has come from.

A friend brought me a copy of this booklet which had been deposited in her letter box and it makes for ghastly reading.

I actually took it to my Year 13 History class to use as an example of how to properly detect fact from misinformation. This booklet is full of inflammatory cartoons, language about ‘maorifying’ New Zealand, stoking fear about ‘tribal takeovers’. It is also full of ‘quotes’ that are misrepresenting what the person said. One such example was a quote from a Guardian article; the reference was included in a footnote so I followed the footnote and read the article, only to discover that the ‘quote’ was in fact a paraphrase which purposely twisted the meaning to support Batchelor’s claims.

It is one thing to disagree with Co-governance as a philosophy or policy, it is completely another to spread misinformation and deliberately stoke fear of a ‘tribal takeover’.

Why do people want a referendum on the Treaty Principles and why are other people so angry about it?

In brief, the ACT party want a referendum on the Treaty because they argue that the ‘principles’ of the Treaty which appear in legislation are not reflective of the intent and purpose of the Treaty. As Moana Maniapoto said in this excellent discussion: “David [Seymour] isn’t a historian, lawyer or reo expert. When I interviewed him before the election, he refused to name any iwi leader, academic or activist who has advised him. But without a hint of irony, he takes it upon himself to define Te Tiriti.”

The reason that many people are concerned about this proposed referendum is not that there is no place for discussion (or reflection on whether in fact the Treaty Principles simply serve to solidify Crown power), but that we saw what happened in Australia with the Voice referendum. We saw what happened in Brexit. We saw the racism and division stoked up. The platform this would give to those who want to remove protection and equity for Māori is worrying.

What about the Aotearoa New Zealand Histories Curriculum? Isn’t this just ‘maorifying’ education?

I hate that word, ‘maorifying’. I use it because Julian Batchelor’s anti co-governance pamphlet specifically accuses current history classrooms of ‘maorifying’ students.

First let’s deal with the Aotearoa New Zealand Histories Curriculum. This curriculum refresh was initiated with the creation of an advisory group in 2018 and announced to be implemented in 2022 (and then put back a couple of years due to the pandemic). Many schools will be implementing it for the first time next year (2024) but our school has been incorporating it since 2022 (to be fair, we already taught most of these things anyway). It became from 2019 part of an overall education refresh. The new Social Sciences curriculum will be in place from 2027.

One of the prompts for the change was a petition with 10,000 signatures to parliament in 2015 made by students at Otorohanga College to request a day to remember the New Zealand Wars. They expressed concern at how little knowledge most New Zealanders had about this important history.

This is a good moment perhaps to point out that even six years ago, there were many teachers at many schools who were reluctant about even teaching The Treaty, and fewer who actively taught Te Tiriti. I will never forget standing at a Social Science teachers conference with my poster presentation on Teaching Te Tiriti and a sceptical looking older woman peering at the poster then saying glumly, “I suppose I better learn about this.” Part of this is the long standing sneering at our own history (all of it), part of it is ignorance, and another part is fear.

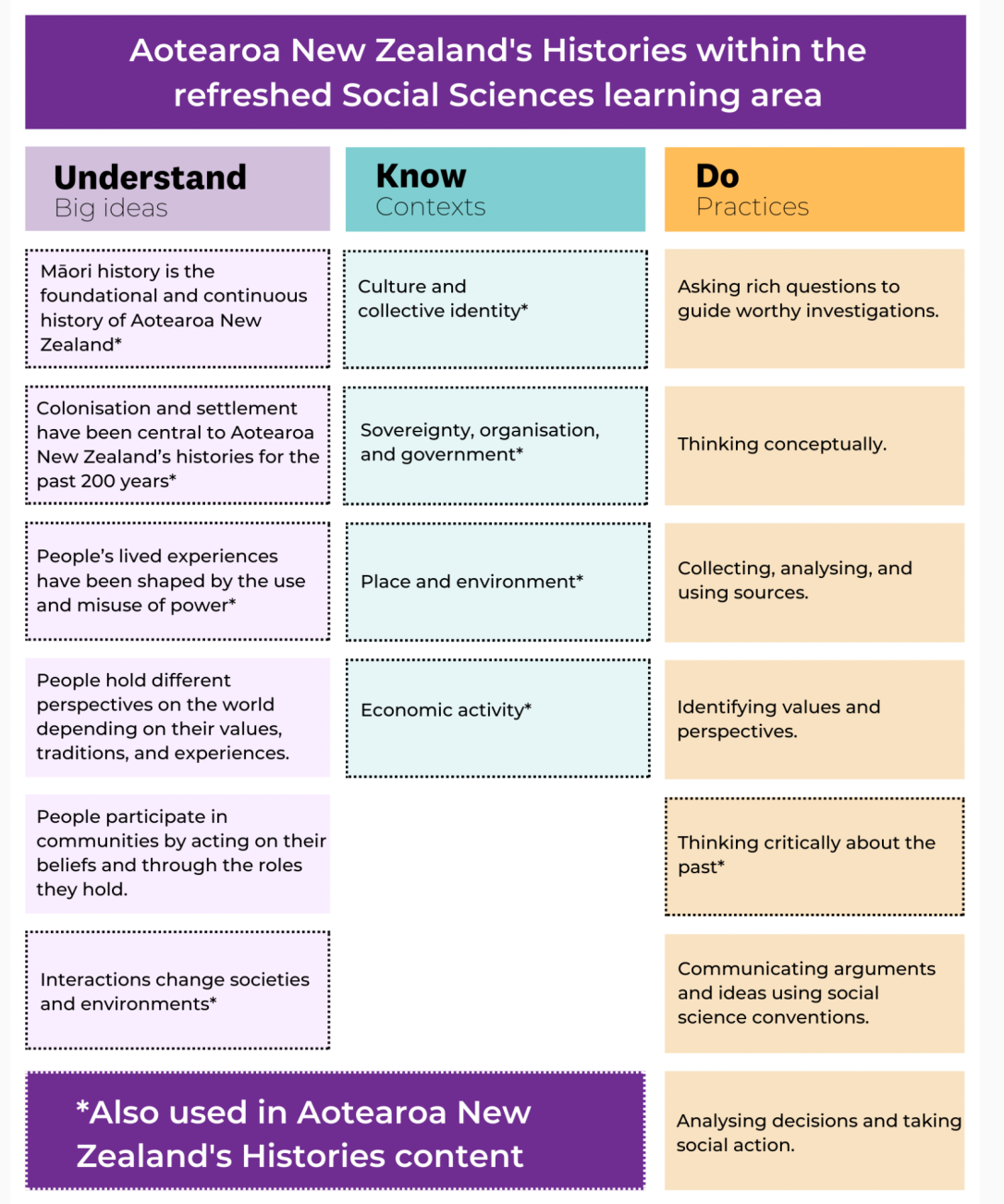

Here is a handy visual overview of the AoNZ Histories Curriculum which you can read more about here:

You can see from this that, despite what the uproar in media would have you believe, Māori history is only one part of a broader whole. Our history is underpinned by the histories of tangata whenua, and of colonisation, but there are many stories that go into creating this tapestry and the aim of the curriculum is to highlight these.

If you are really interested or concerned, you can read the actual curriculum document

For those who have better ways to spend their weekends let me sum up what this ‘divisive’ curriculum intends for students to know by the end of two years of junior social studies in high school:

- immigration schemes and policies over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including the New Zealand Company scheme, Vogel Scheme, the discrimination against Dalmatian migrants, the Chinese Poll Tax, and the impact of these on people and place. Including the Dawn Raids, the White New Zealand policy, and a discussion of whose identity as a New Zealander was reinforced. We also examine how immigration and settlement changed the demographic make up of New Zealand, and the changes to society and the economy from immigration

- our participation in international conflicts, including World Wars One and Two, Vietnam, and our peacekeeping efforts, and how we remember those conflicts.

- The government’s relationship with Māori – specifically through wars over sovereignty, raupatu (confiscation of lands), assimilation via Native Schools, Māori engagement with the political system (from inside and outside the government system), and the impact of the Waitangi Tribunal

- Our involvement in the Pacific – Samoa and independence, protest against French nuclear testing in the pacific, climate change advocacy

- the impact on the environment from people – how settlers changed the landscape through mining, timber trade, dairy farming etc. Building of railways and infrastructure. Conservation of areas of natural beauty, environmental protection and collective action

- The economy – in particular the impacts of global trade and events like the Long Depression, Great Depression, the Waterfront Strike, the development of the Welfare State.

The aim is that key important information about The Treaty which we currently teach in Year 9 or 10 will already be covered by Primary and Intermediate schools.

Much of this many schools like mine already taught. The aim is to bring greater consistency around the country. I would argue that in a time when students watch Tik Tok and become convinced that Giants Are Real, having some consistent accurate history can only be of benefit.

The other key point is that these are not the only things your child will be learning in Social Studies. This part of the curriculum will be sitting alongside the remainder of the Social Sciences curriculum. It is supplementary, not supplanting.

Okay, but what about Mātauranga Māori? Isn’t that trying to switch out facts for stories?

mātauranga Māori simply means Māori knowledge. The implication that all Māori knowledge is myths and stories and non factual is inaccurate.

Any cursory glance at the new Level One standards and curriculums will show you that, in fact, mātauranga Māori is scarcely mentioned in the majority of subjects. In Science, it simply states ‘consider also mātauranga Māori’. NCEA History includes much stronger incorporation of Māori concepts and ways of examining the past, alongside other key elements such as the way power relations shape society and the importance of cause and effect, and the very nature of history as a construct with different perspectives and narratives.

The Science department at my school already seamlessly integrates mātauranga Māori, te reo Māori, and western scientific understandings into, for instance, an engaging holistic exploration of astronomy.

Just like the AoNZ Histories curriculum, the inclusion of mātauranga Māori is not supplanting, but enhancing.

Some Final Thoughts from a history teacher:

Decolonising our History and our teaching go hand in hand.

It might feel overwhelming, confronting, or even frightening, but it doesn’t have to be.

Think of it as embracing additional knowledge and interpretations

Think of it as understanding where our knowledge was and is formed

Think of it as an opportunity to be inclusive, to ensure that everyone has a seat at the table and a voice to be heard

This is a very long post (even longer now I have updated it!) but I find myself unapologetic. It’s not even the tip of the iceberg.

Whilst the vast majority of feedback I received on this post in 2017 was positive, it also brought me to the notice of racist trolls which is why the comments are disabled.

If I’m completely honest, it’s uncomfortable putting myself back in the firing line again, but I strongly believe that this is one of the most important and overdue discussions we as a nation need to have. I’ve always observed that when you replace ignorance and preconceptions with knowledge, understanding and empathy follow.

Thank you for reading 🙂

List of Reports by Clementine Fraser, Submitted to the Waitangi Tribunal

Takahue: Investigation and Alienation report

Nelson Tenths and Motueka Occupation Reserves 1840s-1970s – report

Tuhoe and the Native Land Court 1866-1896 – report

Really excellent. Thorough, clear, and understandable – and extremely reasonable. Thank you Clem.

I particularly like this “So am I supposed to feel guilty for what happened in the past?

No, but you are responsible for what you allow to happen in the present.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent presentation of the questions and the answers are clear and persuasive. Well done

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this! It’s beautifully explained, and addresses the most common issues which people bring up around the Treaty. Would you mind if I shared this with my form class next year?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind words 🙂 I would be most happy for you to share it with your class and whomever else you think might benefit, and am pleased you found it useful!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for writing this! It explains it all so clearly, and covers so many of the issues which people persist in bringing up. Would you mind if I shared this with my form class next year?

LikeLike

Thank you for a very clear explanation!

LikeLike

You’re welcome!

LikeLike

Wow, great article, Clem. This was all new to me, but I feel that you gave a very balanced, clear explanation. It is obviously not the same as apartheid, but definitely a sad undermining of indigenous peoples characteristic of colonisation in many countries, with long-lasting effects. It’s great that you’re working hard to make this history known so that past and current wrongs are addressed while the mistakes of the past are not repeated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you! i really appreciate that!

LikeLike

This is so well written! Thanks you for this amazing resource.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome! I am so glad you found it helpful!

LikeLike